Why does the brain fail?

People tend to believe the human brain is an objective machine capable of perfectly managing us. And yet that belief couldn’t be further from the truth – our brains make so many mistakes, especially in the way we think. Our brains use filters that have evolved with us to help us survive as a species, but what was necessary back when we lived as small groups in caves isn’t always practical or applicable to the modern lives we live today.

These filters in our brain are called cognitive biases. They’re not mistakes in our wiring or the result of neurological mishaps; they have a purpose, and they don’t reflect our levels of intelligence. They’re triggered in all of us under the right circumstances. Essentially, they make us deviate from rational thinking.

Why? For several reasons:

- There is too much information in our day-to-day lives, and the brain needs to process information quickly. To survive, we need to make decisions fast.

- There is not enough information, and the brain needs to decide from sparse data or where there is not enough meaning in the information we receive.

Our brains are powerful, but they are also subject to limitations. So, we are wired to automate our decision making, and that saves us time and energy. If we had to think for hours about every single decision we have to make, we would get far less done.

But how do these cognitive biases look like in practice? Here a few examples:

AUTHORITY BIAS

You can see this one a lot (mis-)used in commercials. Authority bias describes our natural tendency to regard the opinions and instructions of an authority figure as highly influential and important. As such, we are more inclined to follow these instructions. Authority in this sense means not only a leader but an expert, professional, knowledgeable person, doctor, lawyer, scientist, great sports player, teacher, and so on.

This bias has an important meaning for the good. Because we can’t know everything in the world, we have to rely on other people’s the skills and knowledge. We need to trust experts, professionals, doctors, and others, for that matter. But it is good to remind ourselves of the fact that our brain suggests following someone only because of their authority, not necessarily because of the quality of what they have to share. Therefore, double-checking the expert’s intentions, background, or our own reasons why this particular person’s advice seems valuable is helpful in keeping authority bias in check.

Where can you observe this bias? You can probably think of many real-life examples of brutal leaders throughout history that people followed, killed on behalf of, or died for. Leaders might use their authority to their advantage. However, it can also apply to religious leaders that use their influence to persuade their followers. Here again, you might be able to recall some recent events of religiously motivated brutality and war.

But there are hundreds of smaller, daily occurrences. As mentioned, it is often employed in advertising. Actors in white coats (presumably dentists) make recommendations for toothpastes because we regard their opinion as more valuable than a product recommendation from a random person in a commercial. In a successful Dell commercial, Sheldon Cooper (or more precisely, the actor Jim Parsons who plays Sheldon Cooper, the notorious superintelligent character on the TV series, The Big Bang Theory) was selling Dell computers. Does Jim Parsons know anything about computers? Not really, but we associate him with the nerd from the series who knows everything about computers, and thus we tend to trust his advice subconsciously. So, although it is normally very beneficial for you to follow the lead of society’s authority figures, such as lawyers or doctors, we still should reflect on the origin of the authority we ascribe to these people and what exactly they persuade us to do.

In fact, it is easy to fake authority. In a toothpaste commercial, it is enough to put a white coat on someone and the brain subconsciously gives more weight to his/her opinion. Online, sometimes it is enough if somebody claims they are a lawyer, and it becomes less important or obvious if they give deeply misleading advice.

Authority bias is a serious issue in politics. If a certain political figure displays charisma, leadership or other cues we associate with authority, these characteristics are often considered more important than the content of their speech. Not because of the value of their arguments and quality of their credentials, but because of their self-esteem and authority aura. This is one of the reasons why figures like Hitler could secure such broad support. He appealed to people’s innate predisposition to follow and trust authorities. It’s not our fault as it’s how we have been wired since prehistoric times, but we can still do something to minimize it.

What can you do to offset authority bias? Sometimes, just ask yourself: a) Is this really an authority in the field? b) Are there certain motives that could affect the truthfulness of this authority’s opinion? c) Double check why you follow or vote for certain politicians. Is it that you feel they are competent, or do you really know exactly what they stand for? Can you name the real steps, characteristics and policies of these people that prove their competence?

IN-GROUP FAVORITISM OR IN-GROUP–OUT-GROUP BIAS

Ingroup favoritism is one of the most bizarre and common biases. We survive in groups, and that is how nearly all our social and emotional lives as humans have evolved. To be part of and stick with a group provides us protection against the dangers of living alone. Our ancestors needed this as they navigated their natural environments. What evolved alongside this lifestyle is ingroup favoritism, which makes us hold to our own group by all means. It works like this: regardless of the group you identify with (your class, group of closest friends, sport team fans), you develop a tendency to think better of and about nicer things as they relate to the members of “your” group than about members of “other” groups (e.g., the rival team or the people who go to a different school).

It works in all environments. For example, suppose you are a fan of the Manchester United football team and you’re at the match where they play against Barcelona. In that case, you’ll probably downplay any violent or indecent acts done by fans of the team you root for while simultaneously judge more harshly the fans of the opposite team if they do the same thing. The same would go for the players; if your team’s lead player fouls somebody, then you’ll probably regard what they did more leniently and start complaining that the injured player is just acting.

We do this all the time and in all possible environments. It’s such an innate tendency that studies show that people can be randomly assigned to a group with other people they have nothing in common with, even with others they’ve never met before, and yet, once grouped together, they’ll start acting more generously to their group members and more easily develop an antagonistic relationship with members belonging to a different group. This happens for no reason other than this bias being so deeply ingrained in us as humans that it is automatically triggered when we perceive we belong to a group. Hand in hand with this comes the tendency to think less of the members of the other group, an outgroup we don’t belong to. As in the example of football fans, it’s not only thinking that we are better, it also means harshly judging what the other group is doing. We develop a sense of identity at their expense, built on the idea that they are “worse” than us.

As a matter of fact, this is a basis of discrimination – thinking better about oneself and the group where one belongs and thinking much worse about another group, with the consequences being derogating and mistreating the outgroup members in real life.

You can probably imagine how easily this bias is misused. The really challenging thing about cognitive biases is that they are triggered automatically, like a reflex, without our conscious thinking. They are, in fact, a part of our unconscious, so-called automatic thinking. Therefore, you can be influenced by them, and marketing and political communication, in particular, can target your biases to persuade you to buy something or vote for somebody.

Your ingroup-outgroup bias is targeted every time a politician talks about “us” versus “them”, meaning “our people, where we belong”, and those “other people [insert a group], where we don’t belong”. There are literally millions of such examples. You might not remember, but when American president George W. Bush wanted to go to war against the terrorist group Al-Qaeda and consequently attacked Afghanistan and Iraq, he gave an infamous speech:

“Americans are asking: Why do they hate us?”

They hate what they see right here in this chamber: a democratically elected government. Their leaders are self-appointed. They hate our freedoms … They stand against us because we stand in their way.”

This is a technique that appeals to the innate ingroup-outgroup bias. Words like “we”, “us”, “ours” , “they” and “them” are typical examples of speech where the speaker divides society into two categories. The target audience is “us”, the “good guys”, and “they” are the “bad guys”. This division can automatically trigger this bias. Furthermore, it is easy to persuade them that the identified outgroup is a potential danger (we will see that with the negativity bias) and help mobilize Americans for the cause – to fight militarily against “them”.

In fact, there are plenty of politicians from different countries who use ingroup-outgroup bias narratives in their speeches. Here are some examples:

“I do not admit, for instance, that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America or the black people of Australia. I do not admit that a wrong has been done to these people by the fact that a stronger race, a higher-grade race, a more worldly-wise race to put it that way, has come in and taken their place”. The famous former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill said this.

“Your countries are littered with American bases with all the infidels therein and the corruption they spread”. This was said by the Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri, who appealed to Muslims to attack US, European, Israeli and Russian military targets in a speech on the 18th anniversary of the September 11 attacks (the infamous 9/11 attacks on the Twin Towers in Manhattan and other targets on US soil by the terrorist group Al-Qaeda).

“The defense of our values and our identity requires regulation of the Islamic presence and Islamic organizations in Italy”. The Italian far right politician Matteo Salvini said this.

You see? There is always “us”, who are somewhat better and more righteous people, be it British for Churchill, Muslims for al-Zawahiri or Italians for Salvini. And there are always some “bad guys”, not a couple, not just those who do bad stuff, terrorists, killers and so on, but the entire ethnicity, an entire nation. For Churchill, the natives of Australia and America were inferior, for Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri, the inferior group is Americans and those who do not follow their understanding of Islam, while for Salvini, all Muslims are a problem.

Again, this is a technique well-known to Hitler as well. He once said that “The leader of genius must have the ability to make different opponents appear as if they belonged to one category”. This is how you create an easily recognizable outgroup, “them”, “bad guys”, “enemies”, and it’s very easy to blame “them” for some bad things, direct your anger against them and not against your political representatives.

But how can you overcome this ingroup-outgroup tendency? First of all, it is good to already be aware of this bias. Next time you hear a politician claim that it’s “us” versus “them”, consider how it is never as simple as that, and remind yourself of the diversity you can find even within the smallest group you are a part of. Thus, diversity is also true for other groups. Remember that just because you might be unfamiliar with a group, it is not necessarily a threat or something to be afraid of.

CONFIRMATION BIAS

You’ve probably come across confirmation bias before, perhaps without even realizing it. Confirmation bias is the great enemy of science and the learning process. Indeed, research shows that we are very good at researching information but not necessarily evaluating the information’s objectiveness. In fact, we tend to seek out information that confirms what we already think we know about a subject. The stronger we feel about an issue, the more we tend to, more or less subconsciously, disregard facts and information that dispute our existing opinion as well as search for and select only confirmations of our beliefs.

It’s quite like doing a Google search – you’ll be shown results that more or less match what you have written into the search bar before. You’ll receive tons of seemingly relevant information, but you probably didn’t take into account the way you searched for it. For example, suppose you think apples are healthy when trying to research the nutritional value of apples. In that case, you’ll probably type out “apples are healthy” instead of something more neutral, like “health effects of apples.”

We gather and interpret information selectively to affirms our existing beliefs and opinions. We might go as far as to judge the critiques of our beliefs harshly, questioning the sources of data, the author, the facts, and their integrity, while not questioning the sources that affirm our own belief. This is a double standard, and it makes us vulnerable to fake news and misinformation.

Confirmation bias can have serious consequences. For example, suppose a police officer conducting a criminal investigation has a suspicion about a crime, such as who might’ve committed it. In that case, they might judge the evidence they gather in such a way as to devalue that which disputes their own hypothesis while giving more credit to that which confirms their opinion. This is dangerous because it may lead to wrong conclusions. Or, if we already have certain prejudices against groups, for example, the feeling that party politicians are corrupt, then we are more inclined to take notice of sources and reports that confirm these assumptions, and we give them more weight than reports that show us positive examples of politics and politicians’ work.

Confirmation bias is often also the basis of hoaxes and fake news. People might believe these things because it confirms something they already believe in or want to believe in. And this is not something that is a modern phenomenon either. Hoaxes have probably existed as long as people have been living in societies.

One particularly bloody example happened in the Middle Ages. In those times, antisemitism was common. Many Christians at the time blamed Jews for the death of Jesus and held them collectively responsible for it. As early as the Crusades, Jews were gradually restricted from certain professions, required to wear a yellow badge or even expelled from cities and countries (the first expulsion of Jews in Europe happened in England in 1290). In such circumstances, a mysterious disease erupted in the mid-14th century called the Black Death. The disease spread throughout the Old World, killing 20-25 million Europeans and another 35 million Chinese within a decade. In those times, people did not know about the existence of viruses or bacteria, so deterioration of health was often blamed on poisoning. As soon as the disease arrived in Europe in 1346, some blamed the Jews for poisoning wells, what we can now see as an example of a blatant hoax. This medieval hoax was spread by rumors, people telling it to each other in an era without our concept of media. The wells were an important part of the infrastructure of medieval cities – a source of drinking water. Among other ‘confirming’ evidence for the hoax, people argued that Jews were less affected by the disease. This could have been attributed to the fact that Jews lived in segregated areas, did not often go to public wells, or to the fact that their religious practices required stricter hygiene.

This terrible conspiracy spread like wildfire, and as a result, in countries like Germany, Austria, France and Switzerland, Jewish communities were attacked, and were later on victims of violent pogroms. Thousands of Jews died or were expelled because of this lie.

But why did people believe it? Because a lot of prejudice and mistrust was already present in those societies. The conspiracy was an explanation that confirmed what they wanted to believe, to put it simply, that Jews are “bad guys”. The brain prefers an explanation that already confirms what you think because it saves time and energy in comparison to a lengthy reflection you would have to do if your opinion was challenged.

Even now, violent incidents happen because of hoaxes and conspiracies. In India, a video circulated on WhatsApp claiming some men kidnap children. Some 24 people were killed across India because people mistook them for the alleged child kidnappers. In fact, the circulating video was fake – it was heavily edited and was cut from a child safety campaign video in Pakistan.

But what can you do to not fall for confirmation bias? It doesn’t mean that we can’t have convictions and that there is always truth even in the most absurd theories. Some things indeed are just factually wrong, and we can be sure about many things. Keeping confirmation bias in mind can help us be more open to other explanations and put our own firm beliefs to the test. When forming an opinion, try to assess whether you’re basing it on facts. Did you do your research? If you did, was it that another user on Instagram or Twitter wrote something that rang true to your own beliefs, and that is why you feel confirmed in your convictions? Using several official sources can help to ensure that you are truly informed and not duped.

BANDWAGON EFFECT

As mentioned above, humans evolved to live and survive in groups and sticking with the other members of a certain group helped ensure humans belonged to it. The bandwagon effect describes how people tend to take up beliefs, opinions, and ideas the more others have already adopted them. As more people believe in something, others also “hop on the bandwagon,” regardless of the underlying factual evidence. In other words, if we think that a particular opinion is very popular, we’re more inclined to adopt that opinion as well to be part of what we perceive to be the “winning team” due to that opinion’s popularity. When it seems like the majority of the group is doing a certain thing, not doing that thing becomes increasingly difficult.

This is also the basis for fashion trends: the more people see other people wear something, the more they will want to wear it themselves. How often have you disliked a specific type of shoe and eventually bought a pair anyway because all your friends were wearing them? How often have you been scared to admit that you liked an artist and pretended not to like them because your friends were always talking about how much they didn’t like their music?

Human beings have a tendency to conform. It has its perks. Doing what other people are doing essentially saves us time to figure out what it is for ourselves. In trusting other people’s analysis, we don’t have to do the work of going through the research process. It also helps us belong to a group. On the other hand, it puts pressure on us to support opinions or do things we might otherwise dislike or disprove or conform beyond reason.

In a famous experiment that was repeated many times, people were presented with a set of sticks and asked to point out which one was clearly shorter than the others. All group members but one were instructed to persuasively give the wrong answer to the question, which stick is the shortest. It was observed that the one non-instructed person would commonly side with the majority’s opinion even though it was obvious which stick was the shortest. Indeed, 75% of people would opt with the majority and provide a wrong answer to a straightforward question in alignment with our deeply ingrained human instinct to conform.

This phenomenon is very helpful to leverage during political campaigns and voting races: the more a person sees other people voting for a certain party or candidate, the more likely they are to also vote for that party or candidate.

This doesn’t mean that everything one does or likes is because they just follow the crowd. Still, it’s good to bear in mind that our choices can be sometimes affected by others, even without us being aware of it happening, and that our actions can reflect our natural human inclination to want to be a part of a “winning” team. Ironically, there is a tendency to laugh at somebody who we think is a sheep that follows some weird political or commercial trend.

In reality, we all have a tendency to do it. Even political participation is most often based on the inclinations of others around us, our friends, peers or family members.

How can you offset the bandwagon effect? Sometimes take the time to honestly reflect on why you follow a certain trend. Is it because you like it or because your friends do? Recall for yourself why you vote for or are a part of a certain political party – are you actually in line with what they propose, or is your goal to be in line with other people?

On a positive note, you can also use this bias to change your life for the better. Associate yourself with people you admire and respect as you might very well adopt their opinions or emulate their actions. Do this in hopes that you really are “…the average of the five people you spend the most time with,” as a famous quote says. Find a bandwagon you believe in, one you would want to jump on.

NEGATIVITY BIAS

You have surely experienced somebody insulting you or saying something bad about you, perhaps even behind your back, or were unsuccessful in something, and had that experience ruin your mood for a considerably long time. No matter if other things went perfectly or other people said nice things about you; the negative feedback stuck with you like a piece of nasty bubble gum on a shoe.

Obviously, it is normal that some things that happen to us make us feel bad, that we are sometimes sad or suffer due to them, but the human brain works in a way that the negative experiences, and negative emotions that come with them, tend to stick more. One bad insult, negative feedback, or a failed exam ruins our mood with much greater efficacy and longer duration than the joy stemming from success or compliments. According to studies, you need to outweigh one negative thing with three positive things of the same intensity to equal the impact.

This is called negativity bias, and it used to have a vital function for our survival as a species: humans have a natural tendency to learn more from negative information. It was essential to remember the negative things and experiences to avoid them in the future, such as an encounter with a bear in a certain place in a forest. Not going back to that spot increased the chances of survival. Also, learning to avoid a group member who hurled an insult would decrease the chance of souring relations with fellow group members, therefore increasing the chances of survival as remaining part of a group. However, we live in a completely different world now, meaning we don’t actually need the negativity bias for our survival most of the time.

This bias, or brain filter, also means that we focus much faster on negative information than on the positive. This explains why we are drawn to negative news to such a great extent and why they dominate the news cycle. This also explains why we so often hear threat and fear appeals in political messages – they really capture our attention and stick to our memory. And the more negative the portrayal, the more negative feelings and opinions we associate with the topic. This also explains why negative images (threatening, showing violence, or some danger) spread on social media like wildfire.

But how should we tackle negativity bias? As cliché as it may sound, we can prime our brain for positive things. Once a negativity bias is triggered – we receive bad feedback that keeps us down – try to remember it’s because of the negativity bias that we feel this badly and remind ourselves of the positive things that we heard. We also memorize negative things better; therefore, it is good to proactively recall positive moments from time to time; we need to give our brains positive information to focus on.

HOSTILE MEDIA EFFECT

When we read the news, we don’t only read plain text. We digest and interpret the information. By going through our own existing values and predispositions, this processing can distort the message of the original text. But how does this work exactly?

When we have an existing opinion (let’s say, vegetarianism), we tend to think that the media content is biased against our opinion and that it gives much more preference towards the opposite (meat-eating) views. This holds true for the same exact piece of news: if a group of vegetarians and a group of people who despise vegetarianism/loves eating meat read the same commentary, they both might perceive it as favorable to the opposition and being biased against their own point of view.

The explanation is that we interpret the news through the lens of our own prejudices and convictions. That is, if the story does not agree with our concept of reality, it must be biased, corrupted, or inaccurate. At the same time, we are unlikely to see a report that is biased in our favor as unbalanced – we usually do not apply the same standards to news that aligns with our viewpoint. The more we feel strongly about the issue at hand, the more the hostile media effect kicks in.

It happens in other contexts, for example in sports. Sports fans will perceive the referee as biased against their team far more often than they will perceive them as biased in favor of their team. When fans of opposing teams watch the same match, they often see the referee as biased against their own side. This is more than just an emotional bias. In recent studies, fans were asked to count the number of infractions made by either side. They consistently reported their own team committing fewer offenses as it actually did, making the referee seem biased.

This effect happens in the context of mainstream media where we are aware that the issue at hand is viewed by a large number of people. If we consider an article biased, or “hostile”, against our position, we feel that the media reports in a distorted way about an issue that’s important to us and that many people will be influenced by this distorted piece of news. Beware: this is not a question of the quality of certain media. Some outlets are better and some are worse, but mainstream media outlets usually strive to report accurately. Some articles are subjective commentaries, but we are speaking here about general reporting, which should at least try to be objective. But the hostile media effect kicks in even for the most objective of articles. It is an issue of the perception of hostility, not about the objective qualities of a news report.

It can then happen that people feel that this media outlet, or the mainstream media in general, is not objective and has “sold-out” to some interest groups. Consequently, these people can search for alternative sources, often beyond the mainstream media, some of them producing news of dubious quality or character.

Dishonest politicians appeal to this cognitive bias by referring to all media as “hostile” or biased, while in reality it is usually only reporting facts and not omitting the negative details. Look what Donald Trump, the former American president, tweeted about the media:

“What is the purpose of having White House News Conferences when the lamestream Media asks nothing but hostile questions, & then refuses to report the truth or facts accurately. They got record ratings, & American people get nothing but Fake News. Not worth the time & effort!”

Of course, there are issues in media reporting that can be criticized, but Trump admitted that he dislikes the media because they didn’t report how HE wanted them to. Still, this was an effective way to promote the hostile media effect among his supporters – so that they would also distrust the mainstream media.

In fact, we think this about any “referee” – the parent, who is “more often against us” in our fight with siblings, a police officer, or a judge inside of the courtroom. We tend to see every third party that does not completely accept our position as biased against us.

What should we then do? First, it’s good to know the bias exists so that we can be more intentional about trying to consume news from a range of different official sources. All news organizations will have at least some bias, as will every story. But, by gathering information from a diverse range of sources, these biases should be somewhat balanced out. Another strategy is to look at other reactions to the same news. Suppose one feels that a story is biased towards one’s position and supporters of the opposing position also feel the same way. In that case, it’s likely that the article is actually somewhat neutral.

PICTURE SUPERIORITY EFFECT

The picture superiority bias is simple. We normally remember pictures and images better than text. People are likely to remember 10% of what they read three days later. When you add a picture to reinforce that text, they’ll remember roughly 65% of it. This is why commercials and the internet are full of pictures, to get our attention and sell a message that we might remember better.

The preference for pictures over textual information sounds intuitive, but facts and figures support this claim. Our brain only needs 1/10 of a second to understand an image. However, reading 200-250 words takes an average of 60 seconds. People remember visual information 6 times better than the information they have read or heard according to studies. This also translates to how social media works and how social media content gets spread. Infographics (i.e., explanatory pictures with some data) are 200% more often shared online than posts without images, and Facebook posts with images get over 3.2 times more engagement (reactions) than those without images.

We should be aware of this bias because we respond to images so strongly. This is especially important because images can be used to manipulate or persuade us in a way we don’t actually want.

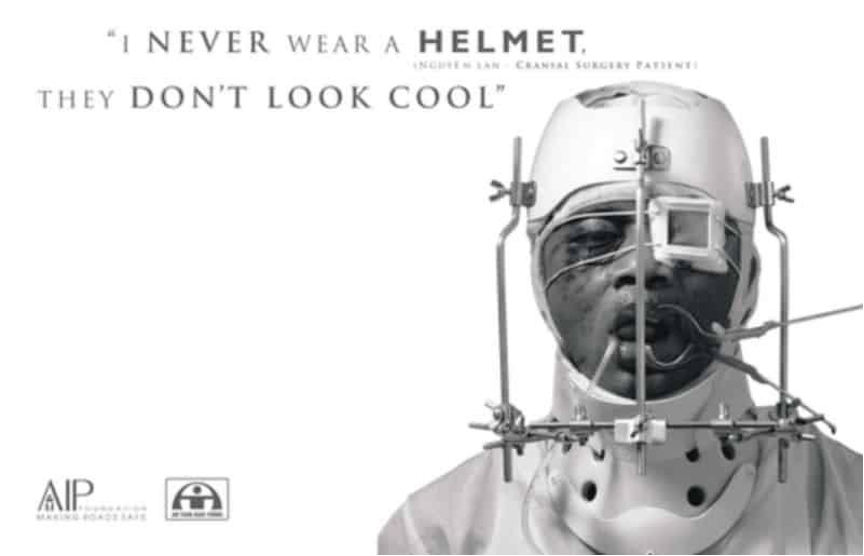

Shocking images can be used for good, as you see in these examples of a social advertisement – against the killing of animals for fur and against riding your bike without a helmet. The picture conveys the message and will make you remember the content of the message.

How can pictures convey meanings or manipulate people? Let’s look at the example of the Islamist terrorist group ISIS. They were active around Iraq and Syria throughout the Iraq War (they first appeared in 2004 and were defeated in 2017) and tried to establish an-Islam based state in these areas. This state was called a “caliphate”, and such caliphates existed before in the past, the last of which was dissolved at the beginning of the 20th century. In their “caliphate”, ISIS ruled through terror, committing atrocities against local populations, the Yazidi minority and LGBT people. The videos of ISIS members beheading “westerners” were a part of ISIS propaganda they posted online. But the imagery ISIS used to portray their Islamic State was far from what was really happening on the ground:

Like in this example, ISIS often used very positive imagery depicting the caliphate as heaven on Earth to appeal to Muslims all around the world to come and join their effort. We usually do not think about imagery accompanying articles or what we see online. We see them in the blink of an eye, and they and their elements swiftly elicit emotions. That’s why the picture superiority effect is so powerful. The danger comes from us processing the cues automatically, with us processing information without really knowing or noticing it. We are targeted by political and other communication constantly, and while the brain grasps the imagery, we might not be fully aware of it.

It’s good to reflect on the images we see on social media or the ones accompanying the news we read given they can greatly impact how we FEEL about a story. When there is an important political issue, pause for a second and see what imagery is used – is it neutral or does it convey a message on its own to influence you?

HUMOR EFFECT

The humor effect means that people remember information better when they perceive it as humorous. For example, a teacher could use the humor effect to help students learn a certain concept through a funny story that illustrates it in practice.

People are generally better able to recall information they perceive as humorous than information that they don’t perceive as amusing. This is because humor enhances people’s memory, whether they are trying to remember verbal information, such as words and sentences, or visual information, such as pictures and videos. Humor leads to increased interest and energy levels. It also reduces negative emotions.

Research suggests that people remember better what is funny because of recall and that watching funny videos works as a mental break from work; people even perform better when doing difficult tasks. In a study, people who watched a funny video clip spent twice as long on a tedious task compared to people who watched neutral or positive (but not funny) videos.

Of course, this bias is repeatedly used in commercials and obviously on the internet. Memes, jokes, and funny videos stick in our memory more easily and are shared much more than written text. But humor can also go the other way around – you’ll better remember some story or memes that criticize someone just because it was funny.

Humor makes unacceptable things more acceptable. We are not talking here about “incorrect” humor, but about rendering certain issues acceptable because you may easier brush them off by saying “oh c’mon, this was just a joke”. These can, for example, take the form of really nasty attacks on political figures.

For example, humor can make racist jokes acceptable. There is no question they are also sometimes funny, but the underlying problem is that people remember them easier (because of the humor effect, we can remember funny things better). Thus, the message the joke conveys is more readily accepted by the audience.

Humor can convey certain things that would look much worse when plainly said or claimed. Therefore, humor is often misused in political speech to say things that might otherwise not be acceptable. It makes a political group look approachable, but with these messages they also set new boundaries of what is okay to say.

It doesn’t mean you should now look suspiciously on all the jokes out there; just be aware of humor in a political context, on satirical, fun pages or on political groups’ pages. Sometimes just take a couple of seconds to think whether the message, without the joke, would not be a bit over the line.

SLEEPER EFFECT OR SOURCE AMNESIA

The sleeper effect means that we typically remember the information we perceive to be funny, negative, scandalous, and so on, but we tend to forget the source of the message. It happens as follows: we hear or see some persuasive message, but it seems suspicious, and, because of that, we deem the source as not credible. We don’t believe the information at first, but with the passage of time, we might forget where we got the information from and only recall what was said. And here comes the twist: once it’s no longer clear where we got the information from, we start believing it! It’s because we have dissociated the message from the messenger, which can increase the persuasiveness.

This is how fake news or all sorts of exaggerated numbers might stick in our memory. We “forget” to be critical about them as we have forgotten about the source’s reliability.

Where do you see this play out in everyday life? It’s the basis of word-of-mouth marketing; product reviews are spread this way. It could have been a friend telling you or a salesperson, or you read a review in a forum. In the moment, you will be clear about who you deem as credible to make a good product recommendation but, later on, you will probably only remember only the essence of the review.

For example, believing the idea vaccines cause autism results from the sleeper effect. There was actually one study that claimed to prove this, but it ended up being discredited and, later, it was dismissed from all scientific sources because the claims made turned out to be false. However, people remember the original information that vaccines cause autism and forget that the source was proven unreliable.

You can also see this bias a lot in political campaigning. There can be a made-up scam, a fake negative story about some candidate, provided by some completely unreliable source. At first, people will distrust the message, but later, when they forget where they heard it, they will remember some vague negative claims against the candidate. So, even if it seemed untrue initially, the dirt could stick to the candidate. This largely affects the undecided voters, who initially dismiss these occurrences as being slanderous attempts, but later, due to the sleeper effect, retain only the memory of the message, not the source, causing them to vote against the defamed candidates.

The sleeper effect is also at the foundation of why fake news is so prevalent. Fake news is made-up or false news that is created to misinform the public or overwhelm it with propaganda. People can distrust the message at first, but later, as time passes, they only retain the information and forget the source. Therefore, the result over time might be that people who at first distrusted information might later end up believing it.

The effect can disappear if people are reminded of the source. The only effective way to overcome any and all effects of the sleeper effect is to question and investigate your knowledge source. If a certain piece of information reaches you, you must determine the soundness of the source, and evaluate the validity of the information before acting on it in any way.

Rosy Retrospection

We all suffer from the bias of rosy retrospection. If you think about your last holiday, what do you imagine? Probably some sandy beach, great time with friends, beautiful sunsets or views from the mountaintop. You will not picture the petty annoyances that ruined your holiday, such as long waiting queues for some monuments, awful food, or conflicts you had with fellow travellers. Those have faded away – the memory of the holiday became rosier – and you remember a disproportionately more positive picture of the event later on.

Thus, rosy retrospection is a biased perspective in that it causes us to judge the past more positively than the present. Many factors contribute to this happening; past emotions are less intense than the present ones and we think about the past more abstractly than about the present, where we have to deal with all sorts of little details, such as doing annoying tasks. It’s also important that we already know how the past story ended. We know how the events turned out, whereas we don’t know how our ventures are going to go in the present. Thus, there is quite a bit of uncertainty and stress involved. For the past? No, there only remains a rosy picture of certainty. It may remind you of nostalgia, but nostalgia is a longing for a past experience and is not necessarily based on a biased perspective. Rosy retrospection is looking at the past through rosy lenses, distorting the real story, and forgetting the negative annoyances.

When people have good memories of the past, they also tend to apply it to political circumstances or the entire society. Often, people have a tendency to judge past governments more positively because they positively associate it with their youth. However, their youthful happiness probably had little to nothing to do with a particular government. This is where political propaganda draws heavily on rosy retrospection, appealing to people’s sentiments that “things were better before.” As we have seen, it’s often just because people forgot about negative aspects as time has passed.

Many politicians love to appeal to this cognitive bias. Every time somebody vows to “return back to the glorious past” or “back to when things were the traditional way”, he/she aims to trigger rosy retrospection – our bias in remembering the past disproportionately more positively. It might have been better, but usually not because of politics. Maybe just because people were younger.

Look at how it can look in a speech given by a politician from Konfederacja, a right-wing Polish political party:

“I want a country of people who do not reject their roots and their faith, do not humiliate their authority figures. Such is the majority of Polish people; they want normality and common sense. They wish to develop Polish tradition in an evolutionary manner, and not by dismissing it for the sake of misunderstood modernity …”

He paints a rosy picture of traditional Poland that is threatened by political and societal changes and progress. It’s innate to the brain to fall for the feeling that it really used to be better. That’s why it’s tricky to base your political convictions on rosy retrospection.

It is worth keeping in mind that the past was never as stress-free as it seems while reflecting on it, and the present is often better than it may feel as you are going through it.

Sources: 1. George W. Bush address: https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/nation/specials/attacked/transcripts/bushaddress_092001.html; 2. Winston Churchill quote: https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-29701767; 3. Ayman Al Zawahiri quote: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/9/11/al-qaeda-leader-urges-attacks-on-the-west-on-9-11; 4. Matteo Salvini quote: https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/matteo_salvini_970885; 5. Antisemitism in Medieval Europe Source: https://www.anumuseum.org.il/blog-items/700-years-before-coronavirus-jewish-life-during-the-black-death-plague/, https://www.britannica.com/topic/anti-Semitism/Anti-Semitism-in-medieval-Europe; 6. How Misinformation on WhatsApp led to a mob killing in India, The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/02/21/how-misinformation-whatsapp-led-deathly-mob-lynching-india/; 7. Melanie Tamble: 7 Tips for Using Visual Content Marketing, https://www.socialmediatoday.com/news/7-tips-for-using-visual-content-marketing/548660/; 8. pictures: www.peta.org, https://www.globalgiving.org; 9. Excerpts from a speech made by one of the politicians from the Konfederacja Party: https://www.pap.pl/aktualnosci/news%2C666017%2Cbosak-polacy-zasluguja-na-kogos-lepszego-niz-duda-czy-trzaskowski.html